An experiment in presenting geometry

ready

under care

downriver

what?

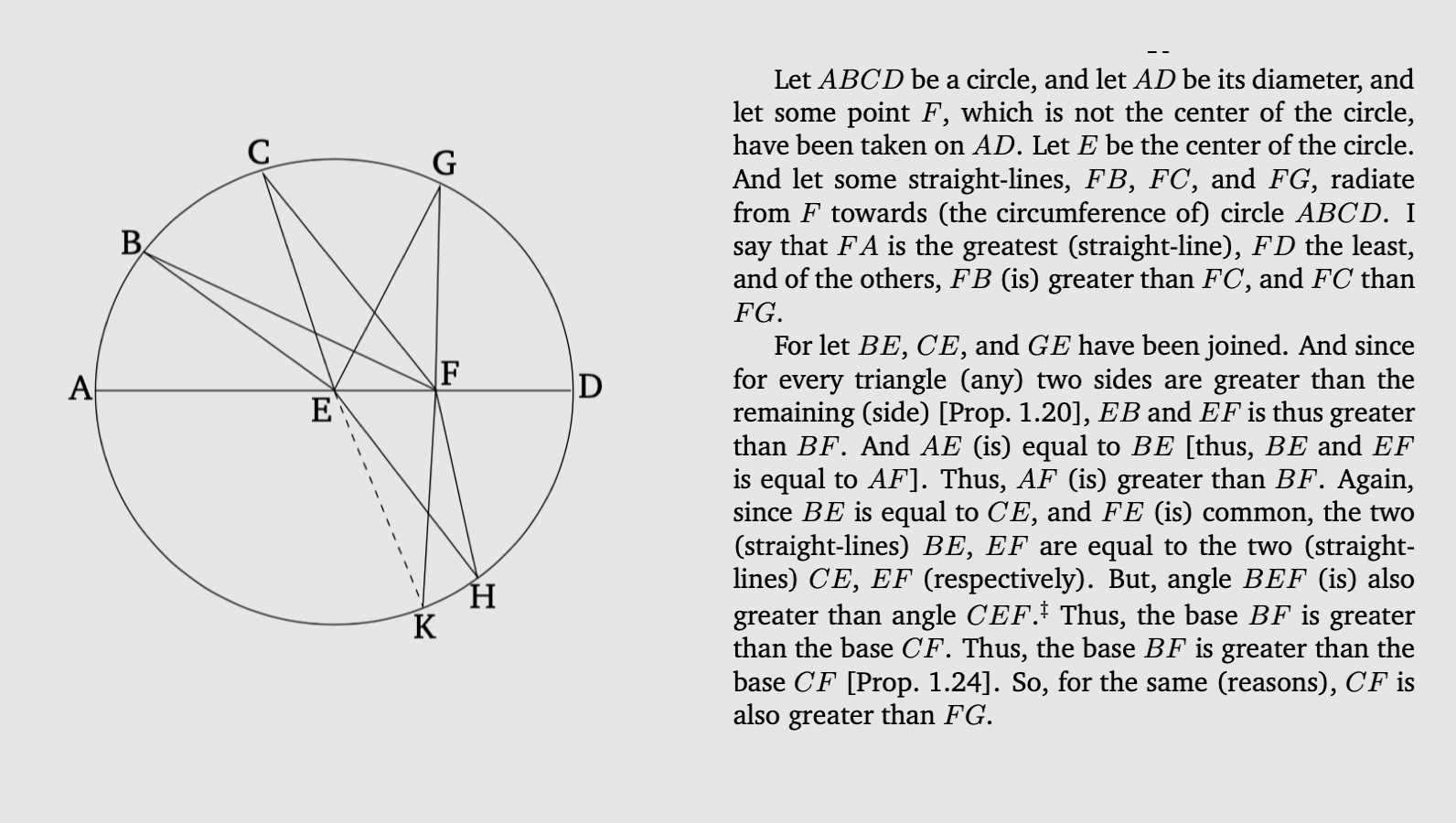

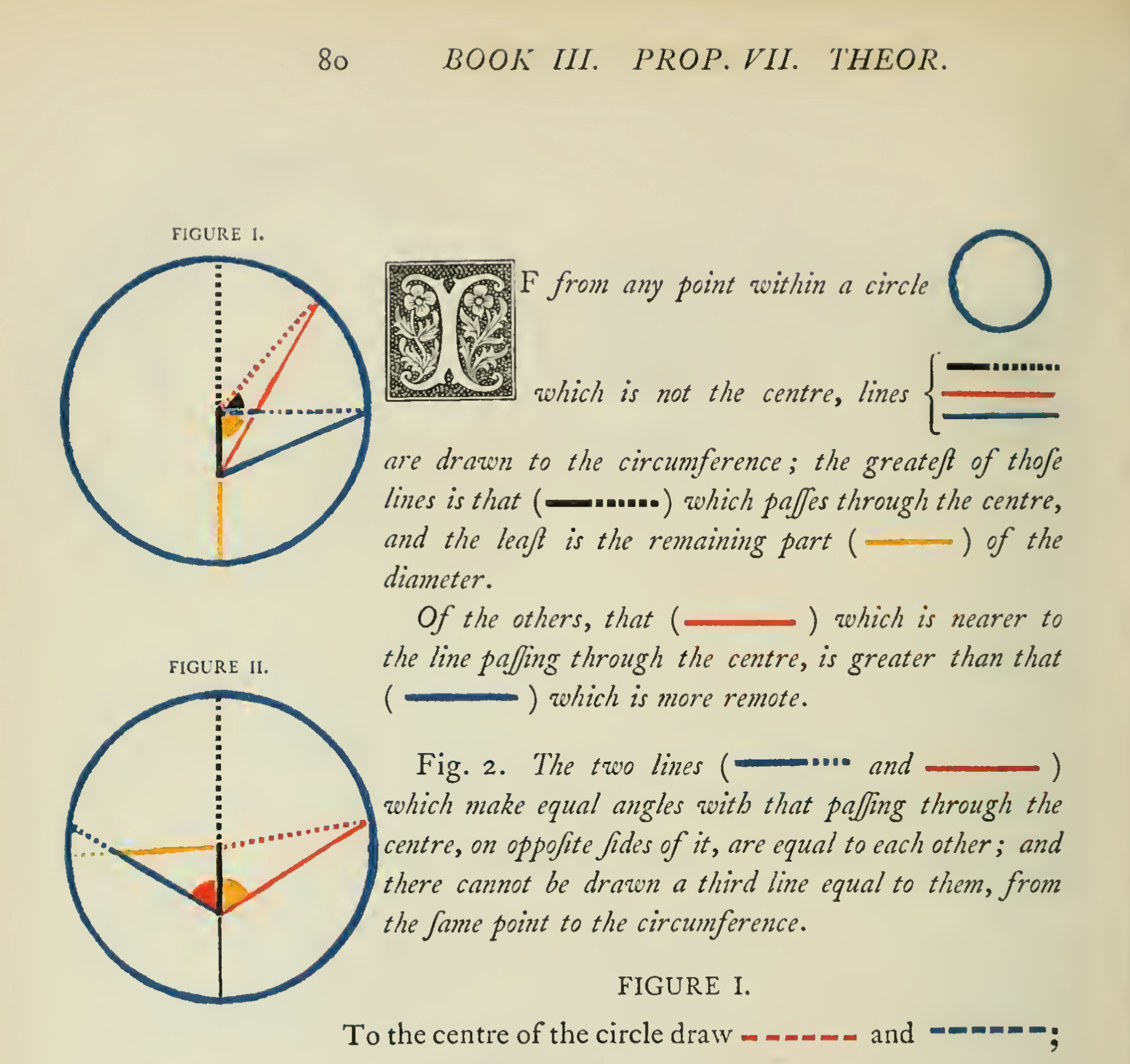

This is a clip from a geometry book. Particularly a translation of the 2300 years old Elements. Reading it requires going back and forth between the figure and the prose multiple times in most of the sentences. Which gets rather tedious and borderline torturous when you need to read again. Coloring it would help greatly.

This is from Oliver Byrne’s work(a digital version can be found at c82.net/euclid). About 180 years ago he made use of colored print and made a phenomenal contribution.

That should bring a question: what can be done with digital displays that gets refreshed 60 times every second?

The usual answer is to record a video. Which dictates a rhytym, isolates fragments, strains potential participation and often turns ridiculous under production costs. Surely films are awesome but their teaching of technical material is not the strong aspect.

It needs to be emphasized here that screens are nothing short of magical. And I request some attention to the potential of intentional simplicity.

Now, follow this short page: elements.ratherthanpaper.com/1.43. And use j/k or down/up on keyboard. Higlights will move along the prose in resonance with the figure. Pointer devices are left on the supporting side.

To compare: Human eye can't distinguish between more than a handful of colors and picking colors for all the objects is not straightforward. But differential brightness on a dynamic screen is plain and simple. Complex figures only get more benefit out of the method. There is no frivolous animation or interactivity to prepare. And, last but not least, it helps people read together or again.

why?

As for ancient geometrical analysis and modern algebra, even apart from the fact that they deal only in highly abstract matters that seem to have no practical application, the former is so closely tied to the consideration of figures that it is unable to exercise the intellect without greatly tiring the imagination, while in the latter case one is so much a slave to certain rules and symbols that it has been turned into a confused and obscure art that bewilders the mind instead of being a form of knowledge that cultivates it.

— R. Descartes, A Discourse on the Method, 1637

This is mathematics at the beginning of modernity from the perspective of the inventor of Analytic Geometry; Introduced as "my method" later in the same book.

Screens are part of the computers for about fifty years now. But couple thousand years of imaginative work on paper determined that screens be an imitation of paper, for the most part. Basic container of data was inherited as files and folders. Much of the private computer was put together in a company that makes photocopy machines. Within which the preview of a print had monumental benefit along with a pointer device and a virtual catalog. Word processors, spreadsheets and slides came to be the most used software and suggested a future as typical products. And we come to look at web pages that were conceived to be available versions of physical documents.

Imitation is mostly effective but it can also be frustrating. But frustrations are a bit difficult to demonstrate. First, It is not obvious how information technology should leave the office and become relevant to life besides facilitation of bureaucracies or consumption of packaged entertainment. Second, criticism of digitized paperwork(i.e. finance) seem to fall on deaf ears. Instead, the new medium is taken as ground to experiment around prevailing institutional dependence and brute specialization that beats their imagination out of people.

Of course, this alone can't leave a dent in the curricular consumption called education. But one question has to be made explicit: What can be done better than on paper? So that we be aware of the cultural momentum and possibly see a course correction.

Care by ratherthanpaper.com as code.